“The pleasure I took in all that was new and strange.” —The Arabian Nights

“It’s clean.” —Major Lawrence

A film version of Dune seems to have the aura of a celestial phenomenon that occurs once every few decades, and with all of the mythic qualities, superstition, and anticipation that surrounds such a thing. A lot can happen in a few decades: children born in 1979 know what life was like before the internet, for instance, and see the world in a fundamentally different way than children born in 1999. How different will the human épistémè be in another 20,000 years? One of the distinctions of Frank Herbert’s novel, first published in 1965, is that the reader is treated to a vision of an interplanetary empire several millennia into the future, where humanity finds itself bound by social conventions and ritual almost completely divorced from our own. The book’s film adaptations (and abandoned and would-be adaptations) have their own storied history, and to his credit, the French-Canadian Denis Villeneuve, whose film version was intended for a 2020 release but was ironically postponed due to a planetary crisis, has accomplished what numerous directors over the last half century—including Alejandro Jodorowsky, Ridley Scott, and Peter Berg—for one reason or another could not. However, in doing so he has accrued a debt to certain aesthetic conventions that have developed in the American studio system—particularly as they pertain to multimillion-dollar productions of what are essentially B-movie genre scripts—over the last twenty years.

Herbert’s novel was one of my favorites as a teenager. My father gave me the Putnam hardcover—its title printed in the signature “Orthodox Herbertarian” typeface—for my fifteenth birthday many moons ago, and it was probably not a coincidence that at the time I had turned the same age as that of the book’s protagonist, Paul Atreides. The story is set in what in our calendar would be the 24th millenium, where feuding aristocratic houses clash over the control of an interplanetary trade in spice, a substance that serves as both a narcotic and a vital fuel source for space travel, and is found in only one place throughout the universe, the desert planet Arrakis. Paul (Timothée Chalamet) is the issue of Duke Leto (Oscar Isaac), who has been appointed the new ruler of Arrakis by a decree issued by Emperor Shaddam IV, supplanting its previous rulers, the Atreides’ rivals House Harkonnen, led by its patriarch, the Baron Vladimir Harkonnen (Stellan Skarsgård). Paul’s mother Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson) is the former student of Gaius (Charlotte Rampling) in the Bene Gesserit Sisterhood—a school that trains women in powers of hypnosis and observation—and is conflicted between her loyalties to the Sisterhood and House Atreides. After being installed on the planet, House Atreides is sabotaged and uprooted by the Harkonnens, who, conspiring with the Sardaukar—the Emperor’s elite military force—hope to gain a foothold on spice production while eliminating the increasingly popular Atreides family. The conspirators kill the Duke, while Paul and Jessica manage to escape to the open desert. It is there that they befriend the Fremen, native to the planet.

This synopsis describes “Book One” comprising about the first half of the novel, which forms the basis of Villeneuve’s film. Herbert’s saga of the Atreides family incorporates much from narratives established in antiquity—specifically the stories of Medea, Oedipus, Moses, and Muhammad. As in Exodus, though Paul was born into wealth he eventually finds his calling as the leader of a displaced people with a long history of exile, and Herbert’s description of Paul’s physical characteristics is not unlike those of the Prophet in various Persian hadiths from the 9th Century (“…he was neither tall nor short, his skin neither very white nor very brown, his hair neither lank nor curly […] his eyes were dark”). Since the book’s publication, Paul story arc—a subject who has removed himself or been forcibly removed from the “civilized” world and who becomes immersed in a more “primitive” or “elemental” culture, finding himself more comfortable in the latter—has been so influential on countless films, from Avatar to Dances with Wolves to even Joe Versus the Volcano, audiences take it for granted as a narrative trope. It follows that the book—together with works by Herbert’s contemporary Ursula Krober LeGuin—had a tangible effect on late-1960s counterculture and its early-1970s fallout in the Anglophone world—comparable to the effect of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago (1973) on young leftists in western Europe at about the same time—as many members of the Baby Boomer generation came from social circumstances not unlike those of Paul: reared in a culture of privilege and ostensibly “rejecting” that culture as young adults for something more “real” and vicariously questioning various structures of political power, if only for a time.

Likewise, the book has always had a particular appeal to adolescent and teenage boys of subsequent generations, echoing Sabina Spielrein’s analogous conception of a boy’s infancy and adolescence as a heroic adventure: a child growing apart from his parents and entering selfhood coinciding with that child’s internal “fantasy world” of being an explorer or discoverer who eventually becomes the conqueror and ruler of a new land. This imagined scenario surrounding the development of a young person—particularly a young man—forms the primary narrative arc of Herbert’s tale: the boy can be taught only so much by his parents and mentors but is eventually obliged to strike out on his own, and ultimately become a different person. Further, the dynamic Herbert established between Paul and Jessica is perhaps one of the earliest modern instances of the ambivalent relationship between a young man and his mother used as an underlying theme of genre fiction that follows this narrative arc. It is perhaps not a coincidence, then, that since the emergence of New Hollywood the two strongest filmgoing demographics in the West for genre cinema—being science fiction, fantasy, horror, and the like—are teenaged boys and middle-aged women.

This might account in part for the legacy of Herbert’s novel, but there is more. A common criticism that readers and viewers have historically leveled at both the books and its film adaptations has been that, narratively, they seem to fail on a “human” level—“human” meaning that a work of fiction presents subjects to whom one can “relate” or situations with which one can “identify.” Yet the story takes place in a very distant future that is fundamentally different from our present. It is also anathema to most contemporary science fiction, exemplars of which are so often meant as “cautionary tales” set “in the not-too-distant future.” One thing to keep in mind however is that while Herbert’s subjects are ostensibly human beings, they are human beings that are the product of thousands of years of accelerated, almost steroidal evolution, informed by the manipulation of bloodlines and by regiments of harsh mental conditioning (to say nothing about Herbert—who died in 1986—not knowing that, half a century after he would write the book, genetic engineering would reach a point where human beings could essentially control their own evolution). Humans in Herbert’s world have achieved powers of telepathy, hypnosis and mind control, but also technology that can shield a person or thing from telepathic detection, savant-like abilities to perform complex math equations without the use of computers, the acute manipulation of hand and facial features, and even the reanimation of corpses. At the same time, humanity has backslid culturally into a state resembling feudal Japan, the waring monarchies of seventeenth-century Europe, and cryptofascism: court intrigue, poison and contraceptives as methods of assassination and sabotage, ritualistic violence between armies sent to their deaths by rival aristocrats, clandestine political power wielded by religious organizations, widespread eugenic programming, few reservations regarding honor killing and incest, and women relegated to the roles of concubines and soothsayers. The first scene in Villeneuve’s film—where Jessica and Paul share breakfast (not in the book and an invention of the screenplay)—encapsulates Herbert’s vision of an oppressive future: “Why do we have to go through all this [ceremony/formality/etc],” Paul asks, “when it’s already been decided?” Jessica’s only response is: “Ceremony.” This allusion to institutional structure is almost negated by the use of the Voice—the manipulation of vocal chords by the speaker in order to immediately influence the listener—in the same scene. The mother, in an almost Oedipal act toward her son, says regarding a glass of water: “If you want it, make me give it to you.” Jessica has trained Paul in the use of the Voice, forbidden among men according to Bene Gesserit teaching. The scene suggests the extent to which institutions have affected populations, and what those populations might do to subvert them.

Dune is, in this regard, about the extent to which human beings are at once the products and servants of various institutions—cultural, political, or otherwise—and perhaps one thing accounting for the “un-relatability” of characters and events in Villeneuve’s film is his fidelity to the source novel when it comes to social divisions: like a melodrama from early modern Europe, despite its scope, the world of Dune is insular, confined to a handful of aristocratic families competing with each other for political power. These are divisions drawn largely along socially-constructed cultural and ethnic lines, which are meant to hide actual social divisions based on economics. The film addresses this, in its way, by turning the Harkonnen family into conventional villains meant to register under late capitalism in North America—specifically an analog for both greedy corporate capitalists and the politicians they buy.

Where does this leave a conventional film hero in the 2020s? The installation of the Atreides family as ostensibly benevolent overseers of spice mining operations on Arrakis—and the imagined optimism that accompanies it—brings to mind Joseph Biden reassuring millionaire campaign donors in June 2019 that “…nothing will fundamentally change.” If one were to “update” or “modernize” Herbert’s story, all of the film’s competing houses would be a villainous monolith, while one would root for the Fremen and spice miners as displaced and disenfranchised guerrilla heroes. Watching the film, I imagined what someone like Pier Paolo Pasolini (who loved contemporary variations of mythical narratives set in desolate, totalitarian landscapes more than anyone) might have thought of the implicit conflict between its social strata. Pasolini and Herbert both flourished around the same time—the mid-1960s through the mid-1970s—and their works were, by varying degrees, responses to Foucaultian power structures present throughout the West at the time. Would Pasolini have wanted the Fremen and spice miners to form a coalition with the Atreides army and the Sardukar in a revolt against the regime that has pitted them all against each other (since even the enforcers of law, in Pasolini’s view, are as much the victims of those structures as the enforced)? Further, one might also see Herbert’s world—where ritualized violence seems to be the only means settling disputes—as being predicated on the male subject’s estrangement from the maternal, as with the perceived “witchcraft” and duplicity of Medea and the Bene Gesserit and the similarity between the fates of Oedipus and Paul.

Oedipal conflict abounds moreso in Villeneuve’s adaptation of Herbert than in any other. In a sequence after the attack on Arrakis’s capital, Arrakeen, where Paul and Jessica have come to realize that Leto is dead, Jessica, having lost her sexual partner, moves psychically closer to her son. She shudders at his touching her, if it is only to fasten her stillsuit. It is at this point in the narrative where the two are searching for the Fremen in the open desert, and where “closeness” between the mater figure and offspring takes on both elements of the transitive (“closer” to their destination) and the intransitive (“closer” to each other). That the film acknowledges in the following scenes that Jessica is pregnant with her and Leto’s daughter Alia adds another dimension to this, given that Paul—in his heightened awareness after his first exposure to the spice—knows that Jessica is pregnant, and in knowing what no one else would know by necessity, stands in for Leto in a paternal role.

Consider also an exchange early in the film between the mother and the son, where Jessica confesses the objectives of the Bene Gesserit organization to Paul, extrapolating the divide between her obligations to her biological and “institutional” families. The scene takes place in a dense fog, not unlike that in a similar sequence in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Red Desert (1964). It is in this scene in both films where the subject is confronted by a conflict between her loyalties and her desires, and on a longer timeline, where the “postmodern” existence popularized by Antonioni in mid-century intersects with Herbert’s subjects conflicted by the imperialist influence on what even after countless millennia remain “human” thoughts and feelings.

A film that did nothing else but address the political or sexual themes in Herbert in the manner comparable to Pasolini or Antonioni, however, would be a remake of Jaws told from the point of view of the shark. Thus, with any large-scale studio epic (or political apparatus or sexual landscape), Villeneuve must abide by marketable narrative codes. The audience is meant to privilege the “good” aristocratic house over the “evil” one, lest there not be an “identifiable” narrative conflict. To seasoned readers of Herbert’s books, however, this is moot relative to what eventually happens to the Atreides family, and if Warner Brothers and Legendary Pictures hope to establish a franchise “tentpole” with Villeneuve’s film, they are in for a surprise with Dune Messiah, set after a twelve-year crusade led by Paul across hundreds of planets that kills several billions of people, and ending with him abandoning his infant offspring. Paul is not a typical “hero.”

Nevertheless, Villeneuve’s Dune is distinguished in its intended and perhaps unavoidable subtext of colonialism, and the response of the colonized. Just as Pasolini had attempted to combine ancient texts with ethnography in works shot in Africa, India, and the Arabian peninsula, Villeneuve approaches the fictional Arrakis with a similar sensibility, shooting largely in Abu Dhabi and Jordan. Consider Villeneuve’s short film Terre des hommes from 1990, made as an episode for the Quebec television show La course destination monde, which would send student filmmakers abroad to film ethnographic footage of peoples encountered, the premise of which was to raise an awareness of impoverished and displaced populations (Villeneuve’s episode incidentally uses music from David Lynch’s Dune on its soundtrack). As early as this, one sees Villeneuve’s conflation of the displaced in Herbert’s novel with those throughout the world. The 2021 film recreates Terre des hommes’s image of a family’s tent shelter in the guise of an ornithopter tarp.

The casting for the Fremen follows suit, as almost all of the speaking roles are occupied by actors of either Black African or Hispanophone descent. Villeneuve’s film eschews issues of “representation” to acknowledges all displaced populations as a grassroots force to be reckoned with, the Fremen being an analog for the downtrodden left out to dry by sociopolitical (ie capitalist, imperialist, colonialist, et al) forces throughout the world, who, having exhausted all “proper” diplomatic channels, are left with no recourse but violent revolution. In Herbert’s vision, colonization and its foils were predicated not on humans’ ability to mobilize machines and weapons, but to weaponize religion and disrupt economies in the process. It may come as no surprise, then, that Dune was infamously the favorite book of Osama bin Laden as a college student. In the wake of the attack on the World Trade Center in 2001, Bin Laden had been quoted as saying that al-Qaida’s objective with the attack was to slowly exhaust the United States’ economy by spurring its government to funnel more and more money—over $8 trillion in the last two decades—into overseas wars and away from nearly everything else. The West’s efforts to exploit foreign populations under the guise of “civilizing” them typically result in those populations eventually fighting back—their way.

This is peripheral to the filmmakers’ longterm objective with Dune, however, being getting a relatively difficult and “un-filmable” book to register in film language. Josh Brolin revealed in a press conference after the premiere at the Venice Film Festival that the cast and crew had been advised to “speak away from the fandom” that surrounds Herbert’s novels in their publicity, likely in an effort to get a global audience unfamiliar with a nearly sixty-year-old book interested or at least intrigued (the morass of studio “making of” featurettes that preceded its release in the United States and China was intended as an “orientation” or “introduction” to its story). The campaign had more to do with tapping into a market of filmgoers inured to the comic book spectacle that has monopolized studio filmmaking over the last decade (which necessarily must cater first to Asian markets, then to domestic markets) rather than a “silent majority” of Herbert devotees around the world (Dune is the best-selling science fiction novel of all time).

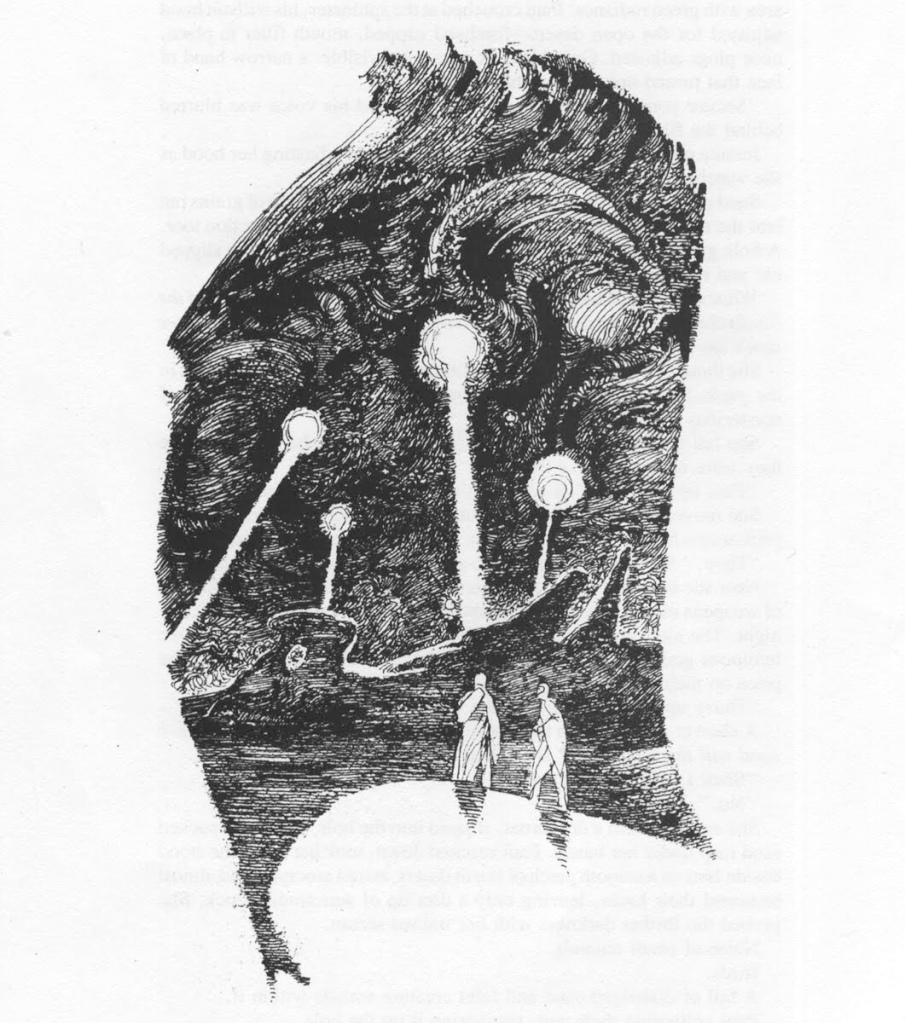

With that in mind, Villeneuve almost by necessity plays along with the monolithic system put before him, and as a result, his Dune has a workmanlike sensibility—in its production design, cinematography, and visual effects—that resembles the state of prestige genre filmmaking today, approaching Herbert in the same way that Christopher Nolan approached the eponymous subject in Batman Begins (2005). Nolan’s film, for better or worse, codified the approach within the American studio system to the “re-imagining” (and the renewal of rights and licensing) of pop culture properties: sleeker, darker, more serious, and more self-important. At the same time, one should acknowledge the influential reach of various illustrators for the covers of science fiction paperbacks published throughout the 1960s and 1970s—particularly John Schoenherr, whose paintings and drawings appeared in The Illustrated Dune in 1978—on Villeneuve’s images, as well as the aesthetic standards first put forth by studios with Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report (2002). Upon its release, Minority Report was praised for its overall slick, “clean” appearance, with critics associating that quality with an “optimistic” vision of the future relative to its default comparative film also based on a Philip K. Dick story, Ridley Scott’s grimy and “pessimistic” (though far more colorful) Blade Runner (1982). The look was later codified by Nolan’s Inception (2010) and Scott’s Prometheus (2012): minimalist, quasi-Brutalist, moderne environments, rendered in a clinical palette with a limited color range. The cinematography by Greig Fraser for Dune falls in with that palette.

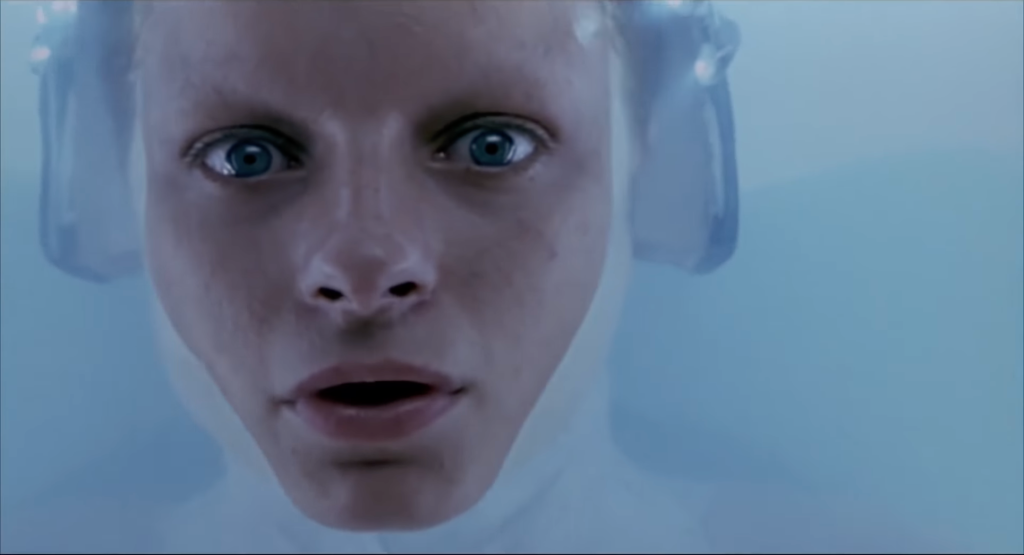

It behooves the viewer to know, however, that this is not a distinctly “American” or even “Western” aesthetic, as it was established by Polish-born cinematographers working in the American studio system since the early 1990s—specifically Janusz Kamiński, who shot Minority Report and Dariusz Wolski, who shot Prometheus. Kamiński—born in Katowice but educated in the United States—and Wolski—an alum of the revered Łódź film school—are both of the generation exposed early on to the Wolfen ORWO film stock procured in the Eastern Bloc after the 1960s—often branded as Sovkolor or Polkolor—which tended to accentuate “cold” or sterile colors as blue, silver, gray, teal, green, turquoise, etc. The look came to be synonymous with “Soviet” or “Eastern European” (and, implicitly, “dystopian”) science fiction, notably Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (1972), Andrzej Żuławski’s On the Silver Globe (1977), and Piotr Szulkin’s O-Bi, O-Ba: The End of Civilization (1985).

This look ran contrary to that of American film stocks, which historically had always based their color palettes on southern California (ironic, then, that George Lucas’s Star Wars (1977) appropriated so much of the anti-utopia imagery of Frank Herbert, Stanislaw Lem, Robert Heinlein, and the rest, using the visual conventions established by the USC Film School). The vestiges of the “Soviet” look emerged in American cinema after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc in 1989, when cinematographers, mostly Polish and of the “Łódź School,” found work in Hollywood: Andrzej Bartkowiak, for instance, managed to make southern California look “cold” and “sterile” with Speed (1994) and Species (1995).

Villeneuve’s film takes its place, in that regard, among a group of perverse, surface-level Hollywood versions of Soviet science fiction that have absorbed the latter’s appearance and style without entirely understanding the purpose of either. One also sees this in the overall production design that has stripped film objects down to geometric forms: space- and aircraft, which at times bear a strong resemblance to monumental war memorials throughout Eastern Europe, and the city and keep of Arrakeen, which draws both from Brut building design and the ancient structures of Giza and Teotihuacán. This is not necessarily the “fault” of the filmmakers either, but merely a part of the épistémè inhabited by genre films made in the last decade.

Hans Zimmer’s film music has followed the same program. Since the early 2000s, Zimmer’s works have become more about instilling a sense of urgency or immediacy (“incidental” music that accompanies onscreen action) in the viewer, rather than establishing a mood or tone for a particular scene. The romantic and tragic themes of The Lion King (1994) and Crimson Tide (1995) have been supplanted by stings, brays, and percussionist pounces that seem better suited to film trailers than to actual films. We know from a 2003 encounter between Zimmer and John Carpenter on the German television show Durch die Nacht mit… that Zimmer admitted to having “borrowed” several of Carpenter’s themes, beginning with the score for his Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), revealing that the composer has in recent years adopted a “rock music” structure based on percussion and distorted modality rather than on melody. The music in Dune—while featuring the occasional striking duduk solo or industrial drone—contains the vestiges of Carpenter and Alan Howarth’s chorals from Prince of Darkness (1987), as well as a variation of Maurice Jarre’s theme from Lawrence of Arabia (1962), and (again returning to Eastern Europe) the percussion and vespers by avant-garde composers György Ligeti and Krzysztof Penderecki.

Yet, the aesthetic distance established by Fraser’s quasi-dystopian photography and Zimmer’s atonal music in its way succors a vision shared by Herbert and Villeneuve alike—that of a “post-human” science fiction more interested in behavior and social ritual than in spaceships and sword fights. In fairness, this is a theme that has preoccupied Villeneuve in one form or another over the last decade. His films Enemy (2013)—where a college instructor meets a man who looks exactly like him—and Blade Runner 2049 (2017)—where androids are ostensibly capable of sexual reproduction—both cast one’s notion of biological identity into question. Dune depicts a practically alien civilization populated by human beings bound by social structures that force their behavior into rigid performative theater. Villeneuve’s film arrives at a less-than-fortunate time when “identifying” with a fictional subject is privileged more than ever over the perverse pleasure of merely regarding the étrangete of a fictional subject, the former arguably not being conducive to viewing a filmic variation on Herbert’s novel. This paradigm favoring identity and identifying pushes the scalpel straight to the marrow of what “speculative fiction” is all about: why must viewers always “see themselves” in the subjects and narrative conventions put forth by genre, when they could merely regard as phenomena a strange world put forth by genre?

Despite this, one cannot by necessity discourage a Hollywood workmanlike sensibility with a novel such as Herbert’s. The opening credits to Jean-Jacques Annaud’s film adaptation of The Name of the Rose (1986) feature a title card reading “A Palimpsest of Umberto Eco’s Novel,” implying that the film will provide only an impression of of a much denser literary source. Villeneuve’s film is a palimpsest as well, working in a similar fashion to pare down scenes to their essential courses of action while filling the margins with Brutalist architectural forms and admittedly grand location footage that follow function (again, Pasolini would have admired the landscapes shot across the Persian Gulf region). In the same key, both films render the notion of “fidelity” in film adaptation of written fiction as being moot altogether, since that notion neglects fundamental differences between the two media. Aside from the occasional description of a landscape (“…it could be a hideous place”), facial feature (“elfin”), or article of clothing (yellow the color of mourning), there is almost nothing “cinematic” about Herbert’s novel cycle, the great expanse and breadth of its world left mostly to the reader’s imagination. There is relatively little dialogue, large portions of the narrative are spent inside characters heads (“…s/he thought”), and as in ancient Greek drama, the “spectacle” of war violence is often referred to after the fact.

This, for the most, runs contrary to the mechanics of narrative cinema. To compare Villeneuve’s film with Lynch’s 1984 version, one finds that the latter is fundamentally different from the book in many ways, particularly the ending and certain liberties taken in order to exploit the use of sound (“weirding modules”), yet better resembles the book’s “literary” aspects as they pertain to characters’ thoughts and motivations. Consider the narration by Irulan, based on literary quotes at the top each chapter of the book (a narrative structure Herbert in turn appropriated from Scheherazade’s storytelling device in The Arabian Nights). On the other hand, Villeneuve’s film often sidesteps awkward internal monologue and expositional dialogue by incorporating the books’ various encrypted “battle languages”—both spoken and signed—conveying plot points and characters’ thoughts so that the viewer may see/hear them while the film’s characters do not.

What emerges is not so much a question of value judgments but what “moments” or “themes” a filmmaker extrapolates. To ask if Don Siegel’s film version of Ernest Hemingway’s The Killers from 1964 is “better” than Robert Siodmak’s from 1946 (or Andrei Tarkovsky’s from 1956) is arguably the wrong question. Is one also asking the wrong question in considering if Villeneuve’s film will have the same “shelf life” as Lynch’s film. Despite the majority opinion of the latter, audiences still ponder it nearly forty years later, if only as a curio, being one of the most bizarre productions ever financed by a major Hollywood studio. Whether or not audiences will feel compelled to return to Villeneuve’s film four decades from now is difficult to say, yet its place in an intertextual network of a seemingly endless supply of soft sci-fi/fantasy and comic book properties—all blanketed by a lowest-common-denominator sameness in photography, design, and visual effects—doesn’t suggest as much. William Friedkin said in 2008: “If we remade The Exorcist now, it [the visual effects] would be a piece of cake…and it would be boring as hell.” If the history of visual culture teaches one anything, it is that a cultural product—a film, painting, piece of furniture, building, article of clothing, etc.—will ultimately reveal less about the artist who made it and more about the culture in which the artist worked in the first place, as the “deposit of a social relationship,” according to Michael Baxandall, owing its posterity largely to the market forces that allowed such production to happen at all. Just as Lynch’s film was a product of its time—Dino de Laurentiis’s “ambitious” productions, the desperate scramble throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s to capitalize on the success of Star Wars—so is Villeneuve’s in how it fills the mould cast by studios over the last two decades: the ubiquitousness of digital film and near-total dependency on CGI, the efforts to establish franchise tentpoles, and an overly self-conscious insistence on its own NPR-friendly allegorical importance.

The viewer is left, then —not just with Villeneuve’s adaptation but also with those that came before it—with a singularity of sorts: an anomalous picture window revealing an alien world that almost stubbornly resists any reasonable semiotic or contemporaneous interpretation. This in part naturally lends itself to genre fiction, and is not necessarily limited to fiction set an imagined future. One doesn’t watch a Kurosawa epic set three centuries ago, for example, to necessarily find an intellectual common ground with the cultural institutions of feudal Japan. Sergio Leone once said regarding his film Once Upon a Time in America (1984): “I wanted to create a world, a plausible world, but one that allows the myth to exist. The myth is everything.” Villeneuve has approximated that myth for devotees of Herbert, if merely inside the aesthetic limits that institutional forces have placed before him at this particular time.

A special thanks to Kephran, Hiram, and Amna.